Surging viewing figures and an array of high-profile success stories means women’s sport is riding high in 2018. So why are so many brands neglecting the sponsorship opportunities of this burgeoning sector?

The past 12 months have been outstanding for British female athletes (as well as female athletes worldwide). From the England women’s cricket team winning the World Cup, to the Lionesses getting to the semi-finals of the UEFA Women’s Euros, and the Red Roses facing New Zealand in the Women’s Rugby World Cup final, 2017 was the year British women took on the world.

The Women's National Football Conference Kicks Off 2019! Get On Board Today!

The recent performance of female sportspeople far outshines the efforts of their male counterparts, and there are more potential successes on the horizon, with the Winter Olympics kicking off in South Korea this month, where at least 50% of Team GB’s medals are expected to be won by female athletes. Contrast that to the slender hopes given to England’s men at this summer’s FIFA World Cup.

Yet brands remain reticent to embrace the opportunities of women’s sports. The most recent figures date back to a study of the market between 2011-2013, which found female sports account for a mere 0.4% of total sports sponsorship. To put that into perspective, global sports sponsorship was worth $106.8bn over those three years, but just $427.2m was spent on women’s sport, so there’s huge opportunity for growth.

The appetite for watching women’s sport is growing too, fuelled by broadcasters such as Channel 4 and ITV bringing international competitions to mainstream TV. Globally, 149.5 million people watched last year’s UEFA Women’s Euros (July-August) according to Nielsen figures, with 87.4 million tuning into the ICC Women’s Cricket World Cup (June-July) and the Women’s Rugby World Cup (August) attracting 33.9 million viewers.

In the UK, more than 4 million people watched the Euros semi-final between England and the Netherlands, while 1.94 million people viewed the Women’s Rugby World Cup final on ITV, compared with just 200,000 who watched the last tournament in 2014.

Brands are not confident enough when it comes to assessing the opportunity of sponsoring women’s sports, argues Laura Weston, board member and trustee of the Women’s Sport Trust, and managing director of Iris Culture. “They’re looking for traditional metrics of sports sponsorship, but that’s completely changing,” she says.

“If you measure women’s sport by the same metrics as men’s sport, it’s going to be difficult for a client to sell in. Whereas if you actually look at the broad opportunity, it is much more accessible than men’s sport and produces much more interesting content. It’s about having a different vision and not just seeing it as a little CSR project.”

This opinion is shared by Colin Banks, head of sponsorship and rewards at energy company SSE, sponsor of the Women’s FA Cup since 2015. He argues that sponsorship is more about engagement than pure brand awareness, which is why women’s sport really delivers.

“There’s still a lot of brands right now that are thinking about how many minutes they are going to get on the telly and ‘what’s my brand awareness going to be?’ Actually, that’s advertising, not sponsorship,” says Banks.

“I would rather have 10 people be incredibly positive about my brand than 100 people just knowing about it, because that actually makes a difference. It’s about saying I know who you are and I know who you stand for. The general public actually care about this stuff, so if you want to change people’s opinions of your brand, get involved.”

Early adopters are seeing the benefits

A number of brands have got in early and carved out a space for themselves in the women’s sport sponsorship market, from Investec with England women’s hockey, to Kia with England women’s cricket and Vitality in England netball.

SSE analysed the sponsorship opportunities for nine women’s sports before opting for football. The Football Association’s decision to bring the Women’s FA Cup Final to Wembley was a major draw, as was the sport’s ability to help the brand make a real statement.

“There are some sports you can invest in and you get your sponsorship benefit, but it’s quite a saturated market, whereas we felt within women’s football it wasn’t that saturated. We could make a pretty big impact in terms of the investment and make a difference,” Banks explains.

SSE has experienced a wave of support from both consumers and staff since signing the four-year deal with the Women’s FA Cup in 2015. Audiences for the event have grown over the past two years, with the 2017 final attracting a record crowd of more than 35,000 and more than a million watching at home. SSE also helped negotiate the deal for kids to go free to the final, targeting families rather than specifically men or women.

“It’s still football and it is the most popular sport in the country, but the women’s game has a family feel and a different dynamic, which is very inclusive. Of course, families and women go to watch men’s football, but it feels a little more male-orientated and more tribal,” Banks adds.

Another prominent supporter of women’s sport is O2, which in 2016 negotiated a new four-year deal with the Rugby Football Union (RFU) spanning men’s and women’s rugby. For head of sponsorship Gareth Griffiths, getting involved with the England women’s team, the Red Roses, was a no-brainer.

“We’re a mass consumer brand and we don’t care about gender. Whether we support a men’s team or a women’s team, it is sport to us,” he explains. “For the Old Mutual Wealth Series [of international matches] we had the men and women appear together in one, standalone piece of creative to represent our England Rugby partnership. That was really innovative.”

O2 expanded its Wear the Rose campaign to the Red Roses in August, tapping into the power of the team’s fervent fan base known as the Rose Army. When the England team made it to the World Cup Final, O2 moved the Wear the Rose campaign from social to TV.

In total, the film reached five million people across video-on-demand and YouTube, as well as more than two million people during the final on ITV. Overall, the O2 campaign drove over two million acts of support for the Red Roses.

Although in the past female sport has not received the same broadcast exposure as men’s, Griffiths believes things are changing.

“I’ve seen a real shift over the past 18 months in women’s cricket, football and rugby. There’s a noticeable increase in the reporting and coverage across lots of different media, not just broadcast,” he says.

“The fact that ITV got behind the women and put the final on primetime ITV was fantastic. I’m delighted they did and I want to see them doing it more.”

Different metrics are needed to measure success

Pivoting to women’s sports sponsorship means brands taking a different view on the metrics by moving away from the traditional measures of success.

Social media has been instrumental in disrupting the metrics, says Weston, who sees the old-school rate card of rights and perimeter boards at matches as becoming obsolete.

Griffiths admits that it is more challenging to develop a business case for a women’s sport sponsorship deal, meaning brands must appreciate that a women’s deal will not offer the same broadcast reach. Instead, he advises brands to look at the return that can be made on the game’s social footprint.

Team GB CEO Bill Sweeney agrees the media profile of sport is changing thanks to social, meaning the days of slapping your logo on a shirt and getting TV exposure are dead.

“Most brands are now thinking that if they’re going to invest in something, it needs to resonate with their values and it needs to ideally be purpose driven in an authentic way,” says Sweeney.

“Now partnerships with commercial entities revolve a lot around grassroots opportunities, societal partnerships and getting engaged with local communities. Those campaigns tend to be much more meaningful in terms of the impact they have on corporate performance and employee engagement.”

Around the Winter Olympics, Team GB has worked with partners such as DFS, Adidas and Aldi on finding the athletes that best represent their values. Aldi, for example, has selected a range of athletes to work with for the Winter Games, most of whom are female.

When investment company Old Mutual Wealth negotiated its sponsorship of the England rugby internationals two years ago, the deal was specifically drawn up to include the men’s and women’s game. Head of sponsorship Mike Mainwaring believes brands are moving beyond purely commercially driven metrics in a bid to become more representative of their customers.

“In the past, it has been a commercially driven perspective of, ‘if we’re investing, where’s the best place to put the investment?’ Women’s sport hasn’t had the platform from a broadcast perspective, so it hasn’t necessarily had the eyeballs watching it,” says Mainwaring.

“If you look at a sport like football where the numbers have increased exponentially over the past 20 years, the number of eyeballs watching has driven sponsorship revenues. Women’s sport has not been represented in the same way, but now rights holders are under more pressure from sponsors. There has been a societal change and people have woken up, especially over the past five years.”

Although women’s sport is indeed claiming a greater share of the broadcast audience, a historic lack of exposure has forced female sports teams to be inventive, circumventing traditional media and in many cases leapfrogging the men’s game in terms of innovation.

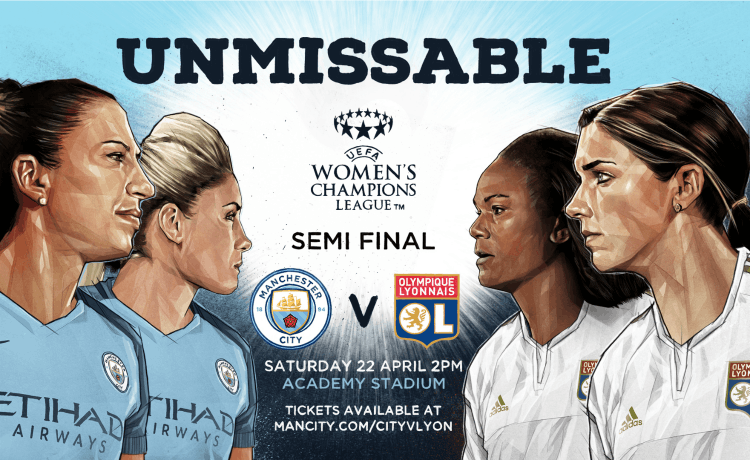

Manchester City Women’s FC, for example, was the first football club in the UK to stream a competitive game on Facebook Live in the summer of 2016. The live streaming extended to the Women’s Champions League as, unlike in the men’s game, the women’s team owns the marketing rights for its matches up until the final.

“For the three games in the Champions League we played at home, we had a reach of around 12 million people [on Facebook Live], something that we did in partnership with Nissan,” explains Manchester City head of women’s football, Gavin Makel.

“We want to push the boundaries as a football club and we have an opportunity in the women’s game to do more. We put a mic on [team captain] Steph Houghton once in a pre-season friendly. Would we do that in a competitive fixture? Probably not, but it was an interesting piece of content.”

Understanding the audiences

One argument often preventing female sports from receiving TV coverage is that there is no demand from audiences. Others argue that men historically do not want to watch women’s sports as they find it slower and less enjoyable. Statistics show both these arguments could not be further from the truth.

According to Nielsen, 56% of the TV audience for the Women’s Rugby World Cup final were male versus 44% female, while the viewers of the Women’s Euros semi-final were split 58% male to 42% female.

Manchester City WFC, an integral part of the City Football Group spanning Manchester City, Melbourne City FC and New York City FC, has a dedicated fan base both home and abroad. This fan base contains a large proportion of male fans, as well as women and children.

“There’s always the perception that women’s sport is for women and yes that is the case in terms of young families and young girls that do go to the games and sporting events, but actually there’s a great percentage of men and young boys who attend our games as well,” says Makel.

“It’s probably around 60% male to 40% female, so that makes us change our way of thinking when we are marketing the women’s team and making sure what we provide on match day caters for different types of audiences, whether that be families, a young girl or a core football fan.”

On the cricket side, 93% of sports fans questioned following the ICC Women’s World Cup 2017 said the tournament represented the best ever standards of cricket, while 67% said they will now follow women’s cricket more closely, according to data collected by Nielsen.

Furthermore, 91% of respondents said they found women’s matches exciting to watch on TV.

Forty-five per cent of people purchasing tickets for the ICC Women’s World Cup tournament were women, according to the England Cricket Board (ECB) statistics, while 24,000 tickets sold (32% of tickets sales) were for children. Of the 26,500 attendance at the World Cup final at Lord’s, 34% of tickets were sold to women, the highest female sales for an international cricket match in England and Wales.

ECB’s head of marketing Rob Calder is conscious that to secure the long-term future of cricket, all its marketing activities should connect with as wide an audience as possible.

“Sport has to compete with the broader leisure industry and it’s an absolute fact that our addressable audience has got to include men, women and children moving forward if we’re going to survive and flourish,” says Calder.

“We have got to be somewhere where families want to come and mums want to bring their kids, just as much as dads do. Everything we’ve got that’s future-facing is about how we ensure we appeal to significantly more women and the Women’s World Cup final was a fantastic beacon demonstrating that.”

Through segmentation the ECB found that more than 70% of men in its most fanatical segment expressed an interest in women’s cricket, a key demographic to pass their love of the game on to the next generation. ECB tapped into this idea with its ‘Go Boldly’ campaign around the Women’s World Cup, creating video content with the parents of the England players discussing how their girls got into the game.

Look out for further features discussing the opportunities of women’s sports sponsorship being published over the next week.